- Home

- L. D. Culliford

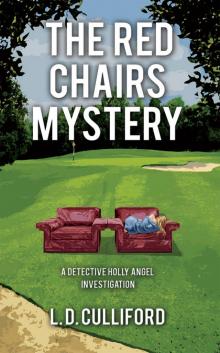

The Red Chairs Mystery Page 2

The Red Chairs Mystery Read online

Page 2

Once past the water on the right, they turned and followed Archie and Ella’s route uphill beyond the fourth green, cutting back then down the fifth after rounding an extensive patch of gorse shrubbery. They soon reached a white van parked off the fairway, emblazoned with the words ‘Technical Medical Unit’ and the emblem of Sussex Police. Beside it, a uniformed police officer stood on guard, carrying a clip-board to record the names and details of all who entered the cordoned off area. Holly made the Colonel stop the golf-cart, gave their names, and noted that a Police Surgeon had already attended and declared life extinct. They were still a few yards short of the taped-off scene. Holly insisted on going ahead on her own. ‘I’ve been close enough to those chairs already’, replied the former soldier. ‘I’ve seen things in my time, but this is still rather grim… I don’t need to go ringside again, thanks’.

A photographer in white coveralls was taking shots from different angles as Holly approached the crime site. Another, similarly attired forensic officer from the Chichester branch stood by ready to erect a tent over the corpse and out-of-place furniture before the pair continued their meticulous work.

Holly suited up and went forward, stepping onto the duck-boards around the scene. She bent over, looking carefully at the red armchairs and their contents. She could see the chairs were worn and scuffed in places, and the deceased woman was probably not as young as Archie Hunter had reported to the first officer on the scene. She looked closely at the dressing gown, noticing how the corpse’s right arm alone was correctly inserted into the sleeve, and how the rest of the garment had been pulled loosely around, over the left shoulder, to cover the torso and tops of the legs. Its edges were frayed, and the clenched fingers of the left hand held tightly to the chest were clearly visible. Had the wind disturbed the cloth, she wondered, or had whoever placed it there done so hurriedly, without due care for the poor woman’s modesty?

Holly took photos for storage on her phone, useful for showing to people who might possibly identify the sorry, almost skeletal corpse; and she asked the photographer to follow the body to the hospital in Chichester, where it would be examined later, to get better shots of the face and any other identifying features.

Extracting a notebook and pen from the dark brown leather bag carried over her shoulder, she began writing down the key questions:

Who is this woman?

When did she die? Where and how did she die?

Had she been starved or tortured?

Was she murdered?

How did she get here?

Who moved her?

The chairs… How were they brought and placed here?

Why?

Circling the last question with a firm stroke of the biro, Holly looked up again to survey the wider scene. The golf course boundary to the south was marked by low mesh rabbit fencing that appeared intact. There were medium-size birch trees and tall conifers forming a loose barrier inside the fence, beneath them an irregular landscape of bare earth, gorse bushes and general scrubland. Beyond, there was further woodland and a sunlit clearing where movement suddenly caught Holly’s eye. Two or three small deer and a larger buck with antlers stood alert, then quickly disappeared into the shadows beneath the trees.

‘I must get out into nature more often’, she thought, taking a deep breath as a green woodpecker flew east to west in long low swooping arcs across her gaze. The bird’s movement carried her eyes further to the right, along the line of the fence. A large bracken-covered bank obscured her view of the green and whatever lay beyond. Advancing past the near bunker into the long grass of the rough, she beckoned to Peter Harding and climbed aboard the buggy as it approached.

‘Let’s take a look’, she said, pointing. ‘Could there be a way in and out of the course over there?’ ‘There used to be, I believe’, the Colonel replied. ‘Before my time… When everything was new and only the first nine holes were open, some members used to drive out here along Stave Lane and start play at the sixth. That way, you can get more people onto the course first thing. They would get held up again, of course, when they got back to the clubhouse and had to start again at the first; but that’s golfers for you, always a little impatient. Some members still use it when we play shotgun-start competitions.’

‘What does that mean?’ Holly was intrigued. ‘I hope you’ve got a licence’, she said, only half-joking. ‘And that no-one gets hurt.’

‘Oh, no… Not at all.’ The secretary was quick to reassure her. ‘A shotgun start is when teams of four golfers are stationed on each of the eighteen holes and start play simultaneously. It doesn’t happen at this club very often. It’s not popular… Takes a long time to get everybody round and then there’s an almighty crush in the changing-room and the showers when play finishes… The signal used to be a shot from a shotgun into the air, but these days we just use a siren… And we don’t need a licence for that.’

‘So there is a gate and car park somewhere near here’, Holly answered. ‘Yes’, said the Colonel. ’Over there.’

They manoeuvred around the bunker, keeping to the long grass. When the buggy drew level with the bracken-covered mound, Holly could see a gap in the trees framing a broad footpath. ‘Stop here’, she said and alighted. ‘Wait for me.’

There was little wind. The silence was broken only by the repetitive high-pitched call of a chiffchaff high in one of the birches. A cloud drifted in front of the sun, darkening the scene as Holly advanced carefully, eyes fixed on the terrain, looking for clues of vehicular access. The path widened beneath the trees, and then opened out into a small clearing, beyond which a narrow lane could be seen. The exit was marked by a sturdy, white-painted gate stained with algae, but this was open, pulled right back against the boundary fence. She could just make out the initials ‘GGC’ on the top bar, over-painted in white. Near the gate was a neatly-stacked pile of birch logs, and nearby a smaller pile of green-keeper’s waste, tining plugs and grass cuttings, partially rotted down. There were a few small puddles in the clearing, and there were many tyre tracks visible, especially near the lane; but Holly was disappointed. If the vehicle carrying the two chairs and the dead woman had left distinctive marks here, it seemed unlikely that they would stand out from all the other indentations. Across Stave Lane a low bank led to a stone wall edging a large field in which sheep were grazing. There was no sign of traffic.

Retracing her steps slowly, Holly made a detour behind the green, scouring the area, including the nearby sixth tee, for clues. Returning to the duck-boards from the northern side, she spent a few minutes talking to the senior of the two forensics men, asking him to tape off the gate and car-parking area, add to their search remit and keep her informed of any findings.

Making her way across to the golf-cart again, she said to the Colonel, ‘The guys say the turf beneath those two chairs is completely dry. That means our corpse arrived before the rain, which is a pity.’ ‘You mean there won’t be any tracks, because the ground was hard and dry before it rained?’ he asked. ‘Yes. And if there were, they could have been washed out anyway.’ ‘Let’s go!’ Holly added. ‘I need to get back to the clubhouse, or somewhere there’s a phone signal.’ ‘Yes Ma’am!’ Peter Harding replied. He said the word deferentially, rhyming with ‘Sam’.

‘Did you recognize the woman, by any chance?’ Holly asked the Colonel a little later as they trundled back up the fairway.

‘No… She wasn’t a member’, he replied.

‘Are there many women in the club?’

‘Quite a few… We’ve about a hundred and fifty on the books, but regular players? I should say only about a third of those. The average age, for both men and lady members, is quite high. We reserve the course for ladies games and competitions on Tuesday mornings and some Thursdays, but not thankfully today.’

Approaching the clubhouse, Holly said she was going to make some calls in her car. The Colonel offered her his office, but she s

aid she preferred the privacy and familiarity of her own regular workplace. ‘It may look like a car to you’, she explained, looking him firmly in the eye, defying him to make fun of her, ‘But it’s where I spend most of my time.’

He had a call to make himself, he was thinking, but it was too early in the day. The club’s founder and Life President, Jamie Royle, who normally kept himself apart from the club’s day-to-day affairs, needed to know what was happening, but it would have to wait a couple of hours.

***

The sun was shining again as, crossing the car park deep in thought, Holly was spotted by one of the less ancient club members. Mark Berger got out of his silver-grey Hyundai Coupe, hoisted a set of care-worn golf clubs over a lean shoulder and strolled over to the Nissan, just as the detective was winding her window down to let in the breeze. She looked up as his shadow fell across her face. ‘Hi! I’m Mark’, he said. ‘I haven’t seen you here before. Are you new?’

Holly was taken off-guard, finding it hard to feel particularly affronted by such a friendly, tall, handsome man with curly ginger hair and very steady blue eyes. ‘No’, she said. ‘I’m only visiting.’

‘That’s a pity’, he replied, thinking how well short, dark hair framed her perfectly-formed face. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Detective Sergeant Holly Angel… Sussex Police’, she said.

‘Cripes!’ Mark replied, laughing. ‘I wasn’t expecting that.’

They looked at each other for a few more seconds. ‘Please go away’, said Holly finally. ‘I’m busy’.

‘Alright, Detective Sergeant!’ said Mark, backing away with a little bow of mock-humility, still smiling. ‘But I may want to talk to you later’, Holly called out as he retreated. She knew that, together with her colleagues in uniform, she would be talking to as many club members as possible over the ensuing days, but wondered still why she had said anything. The impulse had surprised her, but she quickly put it out of her mind.

***

Mark, an estate agent running his own successful, small company, having under-performed in the monthly medal competition the previous weekend, was taking time off work to try and restore his usually reliable golf game. A few minutes after his brief encounter with Holly, he was standing on the practice mat adjusting his grip on the five-iron in his hands at the start of a lesson from his friend, the club’s assistant professional, Kyle Strong.

‘Show me what you’re doing.’ Born in Trinidad, at school in Sussex since the age of twelve, Kyle retained a marked Caribbean accent. The men were in the three-sided hut on the practice ground east of the clubhouse with a plastic bucket full of golf balls between them. Kyle placed one of the neatly dimpled orbs down carefully as Mark took his stance, swung the club rhythmically and propelled the ball in a fine arc over towards the left side of the practice range. The next one went further left still, as did the third; and the next went high, away to the right. Mark was irritated.

‘You see!’ He exclaimed. ‘I’m inconsistent. I’m mostly drawing it to the left, but sometimes it’s a full-blown hook, and then I’ll cut one way out to the right. It’s hopeless!’

‘It’s not hopeless, Mark!’ Kyle sounded patient and confident. ‘It’s just your grip has got a little strong. Your hands are working against each other. When you put the ball back in your stance, it goes one way. When you have it in front a touch, you overcompensate: the clubface turns open as you swing through and forward, and the ball goes off in the other direction. That’s all it is; and we shall soon have it fixed. Open your hands and re-grip them again, like this...

Kyle demonstrated, placing his left hand down carefully first, then covering it in an overlapping fashion with his right. Then he gently corrected Mark as he tried to copy him.

‘Soft hands, remember!’ said Kyle. ‘Always keep your hands soft.’

Twenty minutes later, after learning to relax his grip and place the ball more centrally in his stance, Mark was hitting the ball straighter, not only with the five-iron but with all his clubs, even the driver. As a result, he was happy.

‘You’re a genius’, he said to Kyle. ‘Do you want to play a few holes now? I can’t wait to get on the course and try this out.’

‘Haven’t you heard, Man’, said his friend. ‘The course is closed. They found a dead woman out there this morning. Look!’ He took out his phone and showed Mark Archie’s photo.

‘Wow!’ said his friend. ‘That’s weird! How did you get that picture?’

‘I was alone in the Pro’s shop this morning when old man Hunter came in real upset. He showed it to me’, explained Kyle. ‘He had found the body and taken this photo. While he was phoning the police from the shop land-line, I sent myself a copy from his mobile. I don’t think he knows.’

‘Well, at least that explains the visiting policewoman’, said Mark. ‘Did you meet her?’ His eyebrows were raised, Kyle noticed, and his eyes were widening. ‘Holly, her name is… And very cute she is, too.’

***

Despite the slight breeze, it was too hot in the car. Holly soon got out and stood near the vehicle as she phoned the duty pathologist. ‘Dr Narayan, I want you to come out to inspect the woman’s remains in situ’ as soon as possible’, she said in a firm tone. ‘That’s not going to happen. I’m sorry’, came the abrupt reply. ‘I’m doing a post-mortem for a Coroner’s hearing at two o’clock, so there’s no time. Get the body transferred to the exam room at the mortuary and I’ll take a look later.’

Holly was unhappy. The pathologist, she had always been taught, simply must attend the scene and view the body in situ before organising its removal. However, Dr Peter Narayan was a serious man, and had always previously been reliably thorough, so Holly had to be satisfied that his excuse was genuine. Any complaint she made would likely fall on deaf ears anyway, so she decided to let it go this time, and was soon on the phone to D. I. Garbutt with a preliminary report, asking for the required personnel to help with interviews. Then, glad she had cancelled the lunch with her father, she went back into the clubhouse, passing through the hallway and up the stairs to the Secretary’s office along the corridor. Inside, Holly found Colonel Harding at his desk, telephone in hand, also a short, buxom, neatly-dressed woman, who came straight up to her, hand outstretched in greeting.

‘I’m Valerie Parton, Detective Sergeant’, the woman said primly. ‘Please let me know how I can help. This is just such a terrible thing.’

Holly made an immediate mental note to herself to the effect that, however much the Secretary’s secretary may resemble the singer (with a mane of blonde hair, over-sized bra and such), never to call this woman ‘Dolly’. That would be a cheap and unnecessary mistake. At the same moment, out of the corner of her eye, she noticed the Colonel put the phone down quickly, but said nothing. Forcing herself to say, ‘Thank you, Mrs Parton’, she asked for a list of the club’s staff and members, which, it turned out, had already been carefully prepared for her. ‘Is there somewhere private, where I can interview people?’ she asked.

‘The Committee Room would be best’, said the Colonel, rising from his chair. ‘I’ll take you, shall I?’

***

Back along the corridor, past the head of the staircase on the left, was a large room with an oversized, dark walnut boardroom table occupying the centre. Along the north wall was a magnificent trophy cabinet, full of silverware. ‘We’ve had to put all this in here after a break-in downstairs a couple of years ago’, the Colonel explained. ‘The insurance company now insists the trophies are stored away from public view in a room that’s normally locked.’

‘Were the culprits ever caught?’ Holly asked, wondering if the earlier crime might in some way be connected to the present one. ‘No, they were not’, was the reply.

‘And is that when you installed CCTV?’ Holly continued. ‘I noticed the cameras in the car park and around the clubhouse on my way in… We’ll need the tapes from l

ast night, of course’, she added. ‘I don’t suppose they cover the road approaching the club?’

‘No. They don’t, I’m afraid’, said Peter Harding. ‘I did take a quick look at the tapes before you came, but couldn’t see anything unusual or suspicious after about 8.00 pm yesterday until this morning when the first staff members arrived.’

Holly turned her attention back to the Committee Room. The windows to the west looked out on the practice putting-green and further, across the first tee and the second green, towards the third fairway, partially obscured by an enormous, old but still vibrant oak tree.

Sitting down in the chair at the head of the table, Holly found herself facing a large photographic double-portrait on the wall in front of her. She seemed to recognise one of the two smiling men, standing side-by-side in the sunshine, arms around each others shoulders. They were typically dressed in bright colours with the golf course as a backdrop. The older of the two men had a colourful open umbrella logo on his primrose yellow sports shirt. ‘That’s the famous Arnold Palmer’, Peter Harding was pointing at him and saying, ‘Probably the greatest living golfer… And that’s our President with him: Jamie Royle.’

‘Tell me about him’, said Holly, ‘and about the photo.’

‘It was taken in the autumn of 1983, I think. Jamie had bought the club a couple of years earlier, when the original owners ran into financial difficulties, together with a chunk of the neighbouring farmland. That’s when he had the course enlarged and redesigned by Palmer’s company. The gravel beds were made watertight and filled, for example, and brought into play more. Palmer’s people did all the design work and supervised the construction. Mr Palmer himself only agreed the plans and signed off the contract. He was sent reports and photographs to keep an eye on progress, but had never actually visited the site.

The Red Chairs Mystery

The Red Chairs Mystery